10

Platform one

June/July 2016 |

Unmanned Systems Technology

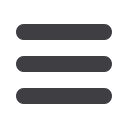

The world’s largest autonomous system

has started two years of trials. Called

Sea Hunter, it is a 40 m ship for tracking

diesel submarines (writes Nick Flaherty).

The sensor and autonomous control

systems were developed by engineering

firm Leidos under contract from US

research agency DARPA, and the vessel

was commissioned for use in April. It

will now undergo two years of testing at

San Diego, California, using a removable

operator control station and a person on

board for safety and reliability testing, but

it is intended for fully autonomous use.

The vessel is designed to stay at

sea for months at a time with up

to 40 tonnes of fuel. It can track a

submarine at speeds of up to 27 knots

in all weather conditions using a hull-

mounted modular sonar system from

Raytheon that is integrated with the

Leidos control system.

It costs around $20,000 a day to

operate, compared with $700,000 a day

for a destroyer, and each ship will cost

around $20m.

Defence

Sea Hunter is designed for submarine tracking

at up to 27 knots in all weather conditions

Sub tracker begins trials

The Southampton University Laser

Sintered Aircraft (SULSA) has been

tested by the Royal Navy in the Antarctic

to help with navigation (writes Rory

Jackson).

It marks the most rigorous trial yet

for the world’s first 3D-printed UAV

since it was unveiled in mid-2011. A

Mobius ActionCam in the nose of the

craft captured the surroundings of ice

patrol ship

HMS Protector

, from which

it was launched, with data recorded to

a microSD card. After completing its

mission, SULSA was retrieved from the

water and later re-launched.

“We intend to add video downlink

capability in the near future, and future

variants may incorporate more thorough

waterproofing and design changes to

enable recovery to a ship,” said Andrew

Lock, enterprise fellow at the university.

The 3 kg craft features elliptical wing

planforms and a geodetic airframe,

printed from Nylon 12 in just five parts

over 24 hours. Such a complex design

would have been expensive and time-

consuming without the combination

of CAD and selective laser sintering,

and the structure snap-fits together in

minutes, requiring no fasteners or tools,

even when attaching payloads.

This enabled operators to strip SULSA

down entirely and re-assemble it after

retrieval. “A bayonet fit, which allowed

quick access to the avionics, would have

been difficult to produce conventionally,”

Lock said, “and a hydrophobic coating

on the avionics meant most components

were re-usable.

“We also heated the pitot tube to cut

the risk of ice build-up by physically

connecting it to the ESC [electronic

speed controller].”

The consistency of the printing process

also allowed previously unflown airframes

to be deployed without needing to trim

control surfaces or adjust autopilot gains.

Navy tests 3D-printed UAV

Assisted navigation